This week is my first time participating in Raimey Gallant‘s Author Toolbox Blog Hop. There are a lot of great blogs here on the hop providing resources to authors, and I’m excited to be taking part. Check at the others at the link above!

Today’s post is the first in a series on dialogue, throughout which we’ll examine its relationships to verisimilitude, conflict, character, and reader engagement. Today, however, we’ll open with a wide lens on this central concept to narrative writing by exploring the three basic forms of incorporating dialogue into our writing.

Let’s give ourselves a bird’s-eye view and see if we can discover the ins and outs of these core structures. We’ll explore effects, styles, and ways of rendering speech. Hopefully we’ll broaden our toolbox a bit. Hopefully we’ll bring a more nuanced intentionality to the dialogue we write.

Three core forms of dialogue

Any time we represent a character’s speech (and many would also lump into this representation of a character’s verbal thoughts), we have a choice between three basic forms. In the following section, we’ll examine these three forms separately, exploring how they’re built in the text itself and their general effects on readers.

Direct discourse (DD)

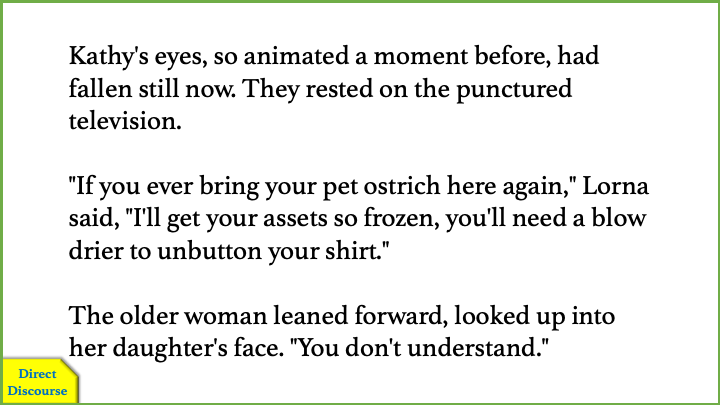

The most common, the form of dialogue we think of immediately, direct discourse is the word-for-word recording of a character’s speech:

How does it work?

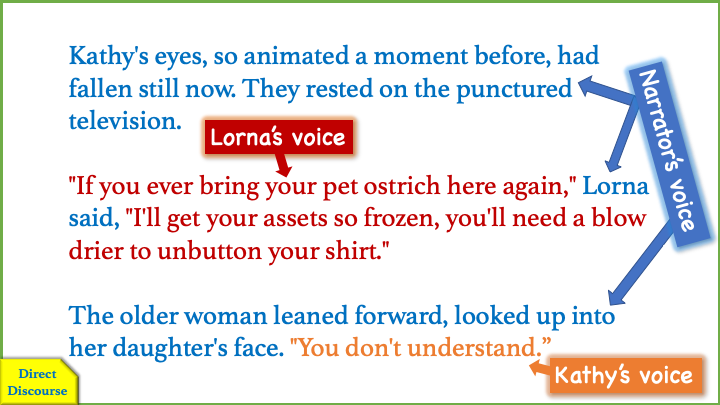

A bit of anatomy here. In this direct discourse example, we have three voices interacting with one another. The narrator’s speech clearly frames the two characters’. We conventionally use quotation marks to identify the hard divisions between different voices, although particular texts might not.

Part of the narrator’s portion involves dialogue tags, the markers denoting which character’s voice is speaking. The presence and placement of dialogue tags is worth paying attention to–the dialogue tag in the middle of a character’s speech creates a pause. Depending on the music of the line, placing the dialogue tag at the beginning or end can also work well.

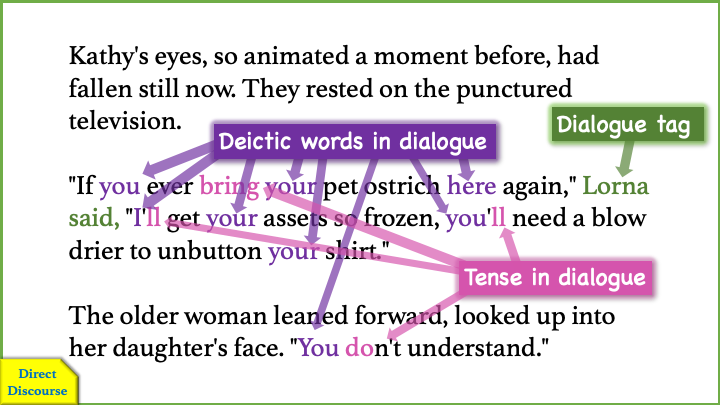

Two other elements of language are also important to identify here, so that we can see what happens to them in the other dialogue forms:

First, deictic words, or deixis. This refers to words whose meaning changes with context. The word “you,” for example, refers to a different person depending on the situation. Personal pronouns, adverbs of place like “here” and “there,” determiners like “this” and “that,” and time words including everything from “soon” to “last week” are all deictic. The “now” in the first paragraph of the example is a deictic word too. I haven’t highlighted it because it’s not relevant for our purposes today.

Second, notice the tense in the dialogue. The narrator and characters may use different tenses, and these will change as the structure of the dialogue is modified.

Effects on the Reader

Clarity

The most cut and dry, the most straightforward, direct discourse has the great advantage of clarity. There is no ambiguity here about what was spoken and what was thought. Unless we get sloppy with our dialogue tags, it is clear who is speaking.

Emphasis

Direct discourse, more than the other two forms of dialogue, emphasizes the spoken word. Conversation is centerpiece here, and in high-conflict scenes like verbal arguments, direct discourse allows these spoken passages to stand out.

Unobtrusiveness

Direct discourse is without doubt the default in modern fiction, and because of its ubiquity, direct discourse does not draw attention to itself. Because it is expected, its effect is largely neutral. The power of this is not to be underestimated. With direct discourse, readers flow through the text easily, without getting caught in tricky ambiguities. Absolutely in the majority of cases, it’s the way to go. Its neutrality is a strength.

Indirect Discourse (ID)

Indirect discourse mediates the dialogue through the narrator’s perspective. We don’t hear the actual voices of the characters; instead, their words are paraphrased or summarized by the narrator.

How does it work?

In the example below, we’ll notice that the two characters’ voices are wholly absent. Their stylistic quirks (most notably here Lorna’s outrageous metaphor) are gone, replaced by the narrator’s more staid expressions:

In Indirect discourse, the narrator also takes over the deixis and tense. An extra dialogue tag appears as well.

Effects on the Reader

Distance from Characters

Indirect discourse has a really interesting ability to put dialogue backstage. Although it’s clear that the character is speaking, primary focus stays with the narrator. Meaning does not change when we switch from direct to indirect discourse, but our relationship to the characters does. There’s a much greater distance, like we are watching the scene from far away, or hearing a description of it more than actually experiencing the scene.

This is the perfect device for situations where we want to obscure characters. If we say, in the above example, that Kathy is our main character, and while Lorna is haranguing her, Kathy is lost in her own other train of thought, then it makes sense for Lorna’s dialogue to be given indirectly.

We might also use indirect discourse juxtaposed with direct discourse in a conversation to show one character’s power over the other:

Jody stood up, and a jet of fire poured out of each ear. "I asked for seventeen pairs of headphones. Why did you bring me eighteen?"

Sammy cowered. She didn't know what to do. She apologized, assured Jody that it wouldn't happen again.

"I know you are trying to do your best," Jody said, "but I can't abide employees who make such basic mistakes."

The injustice brought a tingling to Sammy's eyes, and she wanted to shout, to run out of that room and never return. She knew she didn't have the option. She had to make the best of things right now, as tyrannical as her boss could be. She exhaled, worked her face into a weak smile. She asked if there was anything else she could do.

"Not a thing."

She turned and went.

Conspicuousness and Pacing

Somewhat paradoxically, given the previous discussion, indirect discourse can actually stand out in a text. Because it is unusual, perhaps more common in older literature, indirect discourse can draw attention to itself, slowing the reader down and causing them to linger over a particular line of text.

Where direct discourse encourages a fluid read that can turn into skimming (I know I have been guilty of scanning quickly down a page of direct-discourse dialogue), indirect discourse encourages readers to slow and focus. Skillfully used, this can form part of a broader scheme of pacing, carefully modulating the speed with which readers digest our stories to get the effects we want.

Focus on Narrator

Finally, briefly, if your narrator is a key character in the story (whether first or third person), letting them paraphrase another character’s speech can help us learn about them. Your narrator will report indirect discourse in a way that makes sense to them, and that can be a valuable tool of characterization.

Free Indirect Discourse (FID)

The most complex and versatile way of rendering dialogue is free indirect discourse (note that this is not different from the free indirect style referenced in previous posts on Words Like Trees. I’m using “discourse” today as we’re focusing on representation of speech and thought.).

How does it work?

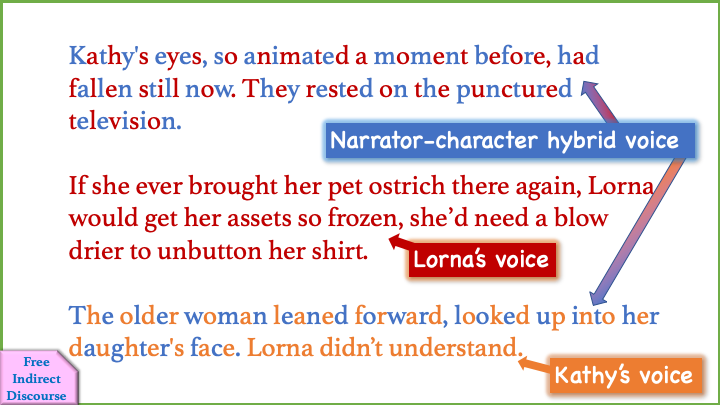

Take a look at our example rendered in free indirect discourse:

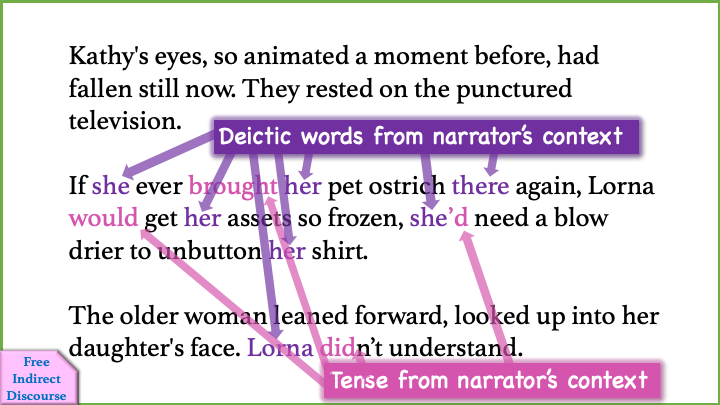

Free indirect discourse moves in the opposite direction of indirect discourse: here, it is the narrator’s voice that is effaced, as the expressions of characters take over the narrative, even though grammatical third person and past tense [if these are what we have chosen for the base POV and tense of the narrative] remain.

One of the odd things about free indirect discourse is that there can arise an ambiguity between what is actually spoken by the character and what is simply thought. Simple narration, such as the first paragraph of the example above, is also ambiguously observation by the narrator or perception of the character. These ambiguities make texts that use free indirect discourse a real intellectual puzzle. Who is speaking? Whose words are whose?

Some have argued that the narrator actually all but disappears in free indirect discourse, present only in the grammatical elements of deixis and tense. Even the dialogue tags have disappeared:

Effects on the Reader

Nuance

The ambiguity discussed above lends free indirect discourse a great sense of subtlety, the kind of passage readers might spend time rereading to figure out. Obviously, as with indirect discourse above, this can affect pacing, which can be advantage or disadvantage.

Free indirect discourse is complex and can lend the whole text a bit of a sophisticated tone. Again, depending on what effect you’re going for, you may or may not want this.

Stream of Consciousness

Although evidence of free indirect discourse can be found going back millennia, its heyday began with the modernists of the Twentieth Century like Joyce and Woolf. These writers used free indirect discourse to explore the thought patterns of characters, and we can do this too. Free indirect discourse is an excellent medium for exploring characters’ thoughts as well as speech. The resulting texts can be confusing, complex, strange, awkward, but done well, free indirect discourse allows us a sensitive eye into our characters’ minds.

Narrative Versatility

Much of what free indirect discourse allows, a first person narrator can accomplish too. However, when we employ a first person narrator we are fixed there; thus, making brief forays out into a more omniscient perspective becomes trickier. If the base of our narrative is instead in third person free indirect discourse, then we are more free to move between perspectives as suits our story.

Irony

Depending on how it is played, free indirect discourse can be an excellent tool for irony and the subtle mocking of characters. This effect can be understood a bit like the way we might use scare-quotes to mock something in everyday conversation. Achieving this can be a bit challenging–you need to establish your narrator earlier with a mocking kind of voice. Then, free indirect discourse can become the perfect vehicle to continue it.

Mixing Forms of Dialogue: Jamaica Kincaid and Langston Hughes

As with many writers’ tools, these three forms of dialogue show at their best when we blend them. We might use direct discourse as a default, drop in a line of indirect discourse when we want something to fly under the radar, shift into free indirect discourse during an introspective moment–the effects these various forms produce, after all, are always contextual. This is their beauty, their versatility, and their challenge.

Let’s take a look at a couple of brief examples to see how these forms of dialogue might function together. First, from Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy:

It was at dinner one night not long after I began to live with them that they began to call me the Visitor. They said I seemed not to be a part of things, as if I didn't live in their house with them, as if they weren't like a family to me, as if I were just passing through, just saying one long Hallo!, and soon would be saying a quick Goodbye! So long! It was very nice! For look at the way I stared at them as they ate, Lewis said. Had I never seen anyone put a forkful of French-cut green beans in his mouth before? This made Mariah laugh, but almost everything Lewis said made Mariah happy and so she would laugh. I didn't laugh, though, and Lewis looked at me, concern on his face. He said, "Poor Visitor, poor Visitor," over and over, a sympathetic tone to his voice...

Kincaid here uses all three forms of dialogue quite deftly. She starts out in indirect discourse: “They said I seemed not to be a part of things”–but as the sentence continues, the phrases become more and more what seem to me like pieces of free indirect discourse: the “soon would be saying a quick Goodbye! So long!”–you can hear the characters bursting through these words, trying to overwhelm Lucy’s narration. This continues as the passage progresses: “For look at the way I stared at them as they ate”–if this were indirect discourse, the “look” would not be written as a command. Then finally, Lewis’s voice has become so strong that it breaks fully into the narrative. “Poor Visitor,” he says in direct discourse, “poor Visitor.” So the power of various characters is demonstrated by the different forms of dialogue. Also notice that the only piece of direct discourse in the paragraph is the one that stands out the most. In fact, it is the title of the first third of the novel.

A second example, here is a passage from Langston Hughes’s short story “Thank You, Ma’am”:

“Do you need somebody to go to the store,” asked the boy, “maybe to get some milk or something?”

“Don’t believe I do,” said the woman, “unless you just want sweet milk yourself. I was going to make cocoa out of this canned milk I got here.”

“That will be fine,” said the boy.

She heated some lima beans and ham she had in the icebox, made the cocoa, and set the table. The woman did not ask the boy anything about where he lived, or his folks, or anything else that would embarrass him. Instead, as they ate, she told him about her job in a hotel beauty-shop that stayed open late, what the work was like, and how all kinds of women came in and out, blondes, red-heads, and Spanish. Then she cut him a half of her ten-cent cake.

“Eat some more, son,” she said.

Most of the dialogue here is reported directly, allowing us to read through at an easy pace, moving the story forward. We slow down briefly in the large paragraph, both because it is large, and perhaps because of the indirect discourse. The indirect discourse about the woman’s job in the beauty-shop also keeps the pace up, however, in another way–this information is not central to the story. Going into detail with direct discourse would distract from the narrative’s trajectory. Hughes chooses to summarize indirectly instead.

Hughes uses dialogue tags beautifully to accentuate natural pauses in the language in the first two paragraphs. The dialogue here is not showy, not complicated as the Lucy example might be. It is straightforward, clear, mostly direct. It does its job well.

Resources

I’ll close with a few resources, which I hope can keep this conversation going. Dialogue is a huge area of exploration, which overlaps so much with characterization, point of view, description, and word choice. In future weeks, we’ll explore some of these avenues.

- My starting point for this post and an excellent (if pretty complex) overview of theoretical ideas about dialogue is from The Living Handbook of Narratology, specifically Brian McHale’s article about speech representation.

- Correctly punctuating direct discourse can be tricky. This article goes over the key rules well.

- This article by Anne R. Allen does a nice job of comparing direct and indirect discourse and highlighting some other concerns about the balance between narration and dialogue, realism, and dialogue tag issues. We’ll explore some of these ideas in future posts in this series.

How do you think about dialogue in your writing? Where do you find yourself using the different forms?

Thanks for stopping by. Best wishes to you all!

Jimmy

What a thorough explanation on dialogue. I use it all the time but I’ve never really given it much thought. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! I felt that way as I was researching and writing the post. Like a lot of things, I suppose, it’s really a rabbit hole! There’s always more to learn…

LikeLike

I really enjoyed the example passages. That first one is soooo funny!!! And way to break down this concept for us! Do you have a facebook author page? If you don’t, no worries, but if you do, please email it to me so that I can tag you when I share your stuff on fb. Thanks!

LikeLike

Thanks, Raimey! Funny is always a plus, especially when grammar is involved.

I don’t have a FB author page… maybe one day. I’m having a great time on the Hop so far – thanks so much for reaching out!

LikeLike

Sound analysis. I admit, prior to reading this, I would have said there was directly quoted dialogue and summarized, but you’re right, indirect has two forms, with very different emphasises.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, Adam! Yeah, they’re weird. And the names of the different forms I don’t think are entirely helpful… so be it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nicely done and welcome to the group. 🙂

Anna from elements of emaginette

LikeLike

Thanks Anna! I’m really enjoying it so far. : )

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, that Handbook of Narratology is going on my to read list. It sounds right up my street.

Free indirect discourse sounds very intriguing and something I’d like to experiment with. Most of my work comes from folktales and I am concerned with retaining a voice that is not too textual, that still seems in a way to be directly from the oral storytellers.

Thanks for giving me much to think about, friend!

LikeLike

Thank you, Sonia! I’m glad you found it helpful. The narratology handbook has been really helping me get past a lot of ideas I’ve taken for granted to see the bigger picture behind. I hope you find it useful!

I think what you say about getting away from a “textual” voice is interesting. Are you writing in first or third person? FID would be a really neat way to explore that! Best of luck.

Thanks for reading, and best wishes!

Jimmy

LikeLike

Wow, such an indepth, thorough look at dialogue. Thanks for an informative post.

LikeLike

I’m glad you found it interesting. : ) Best wishes!

LikeLike

A phenomenal explanation of all three forms here, with some of the clearest explanation of free indirect discourse I’ve seen. Thanks!

LikeLike

Glad you found it useful! Thank you for stopping by. : )

LikeLike

I’m always looking for ways to improve dialogue. Thanks for all the examples and explanations.

Susan Says

LikeLike

Welcome to the hop 🙂

I adore dialogue and prefer direct discourse: My characters would talk all day if I let them! The terminology is completely new to me and you make a good point about using indirect discourse to slow a reader down 🙂

LikeLike

Great post! I haven’t thought much about how dialogue works, only that it does 😉

LikeLike